“The renowned Ethelfleda, who governed the kingdom of Mercia with so good conduct, fortify’d this Town against the Danes who infested her Nation”

[Robert Plot (1686) The Natural History of Staffordshire]

* * *

A number of places in the western midlands of England claim to have been founded by Æthelflæd, the Lady of the Mercians. One such place is Wednesbury, a town lying between Walsall and Dudley. Formerly in the old county of Staffordshire, Wednesbury is now part of the borough of Sandwell in the post-1974 metropolitan county of West Midlands.

Wednesbury’s position in the West Midlands.

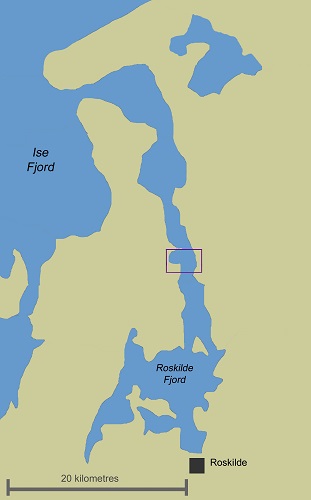

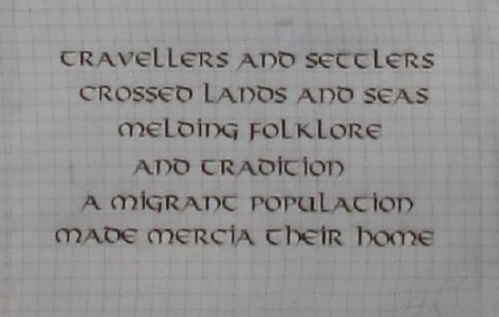

Æthelflæd was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, king of Wessex from 871 to 899. She was born a year or two before her father succeeded to the kingship. Her mother Ealhswith was a Mercian noblewoman of royal ancestry, so Æthelflæd was half-Mercian by blood. At the time of her birth, the old kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England were under relentless pressure from Viking attacks. Mercia had once been a large and powerful kingdom, its rulers holding sway across almost the whole of the midlands. But in the second half of the ninth century it was repeatedly ravaged by the Great Heathen Army, a huge Viking force said to have been comprised mostly of Danes. Indeed, by the mid-880s only a western rump of Mercia remained under English rule. Its steadfast ruler, Lord Æthelred, continued the fight against the Great Heathen Army. Competent in war, he became a redoubtable ally and trusted subordinate of King Alfred. His loyalty was duly rewarded when, sometime in the mid-880s, he received the hand of Alfred’s daughter Æthelflæd in marriage.

Southern Britain in the early 900s.

In the ensuing years, Æthelred and Æthelflæd sought to strengthen their lands against further Viking raids, as well as against the ever-present threat of assault from Wales. They built ‘burhs’ (fortresses and fortified settlements) in strategic locations across western Mercia, often at places that had been important to the kings of pre-Viking times. After Æthelred’s death in 911, Æthelflæd continued the burh-building programme and led the Mercian army on campaign, right up until her own passing in June 918. It is in this seven year period that Wednesbury claims to have been founded by her. Although its name is absent from the Mercian Register – a contemporary record of Æthelflæd’s career in which a number of her burhs are mentioned – this need not preclude a connection. The places named in the Register are unlikely to represent a complete list of all the burhs she founded or re-fortified.

Mercian burhs founded by Æthelflæd: sites identifiable today.

Wednesbury has a long history. The oldest known record of its name comes from 1086, when the royal manor of Wadnesberie was noted in Domesday Book. The name is Old English ‘Woden’s Fort’, recalling the paramount god of the Anglo-Saxons, a pan-Germanic deity whom the Vikings knew as Odin. Woden had been worshipped by the earliest English-speaking settlers in Britain during the fifth, sixth and early seventh centuries, before their conversion to Christianity. It is rare to find his name preserved in a present-day place name. That it survived at all in the post-conversion landscape might seem remarkable, until we note that he was not entirely abandoned by the Christian descendants of the early Anglo-Saxon settlers. Indeed, he was given a new role as an ancestor of kings, his name being included in royal genealogies compiled in the eighth and ninth centuries. Tracing descent from Woden seems to have become a matter of importance for the ruling dynasties of Mercia, Wessex, Northumbria and other kingdoms. Yet it did not compromise their rejection of paganism. The new, post-conversion Woden was not the powerful god of old but a less divine figure whose lineage was now linked to the Old Testament patriarchs Adam and Noah.

St Bartholomew’s on Church Hill, Wednesbury.

The fort of Woden that gave Wednesbury its name is often thought to have originated as an Iron Age hillfort on Church Hill, the high ground where the parish church of St Bartholomew now stands. No ancient fortification can be seen there today but, if it did once exist, it would have been an important feature of the local landscape in the centuries before modern urbanisation. In the 1700s and 1800s, faint remains of old earthworks were indeed said to have been visible on the hilltop. Such claims appear to be consistent with the results of an archaeological excavation undertaken a decade ago, when a large ditch was discovered. This feature seems to belong not to the pre-Roman Iron Age but to the early medieval period, the time of the Anglo-Saxons. It contained framents of pottery that have been dated to the eleventh century, perhaps within a hundred years of Æthelflæd’s death. This raises the possibility that the ditch was first dug in her lifetime, and that it formed part of a fortification that she herself ordered to be built (or rebuilt). If that was the case, then Wednesbury would be one of her unrecorded burhs.

Any discussion of Wednesbury’s early history should also consider that of nearby Wednesfield, another small town lying 4 miles to the north-west. Both places share the same Woden– element in their names and, given their close proximity, it might be more than mere coincidence. Wednesfield, recorded in the late tenth century as Uodnesfeld (‘Woden’s Field’), holds a special place in the history of the Viking Age. In 910, it was the scene of a major battle in which the combined forces of Mercia and Wessex defeated a raiding-army of Danes from Northumbria. The same battle is also placed at Teotaheale or Totanheale, now the village of Tettenhall on the edge of Wolverhampton. Tettenhall lies only 3 miles west of Wednesfield, close enough for us to imagine a battle raging fiercely across the lands in between, with both places caught up in the fighting. Alternatively, the name ‘Woden’s Field’ might originally have referred to an extensive area of felde (‘open ground’) which encompassed Tettenhall and other settlements, including the one that became present-day Wednesfield. If this was the case, then ‘Woden’s Fort’ at Wednesbury might have been so named because it was an important location in the wider district of Woden’s Field, perhaps a prominent landmark. We should also keep in mind the slight possibility that Woden’s Field might have taken its name from Woden’s Fort rather than vice-versa.

Geography of the Tettenhall/Wednesfield campaign, AD 910.

And so we come back to Æthelflæd. In 914, according to the Mercian Register, she built a burh at a place called Eadesbyrig, usually identified as the Iron Age hillfort of Eddisbury in Cheshire. It is thought that she repaired Eddisbury’s ancient ramparts before installing a garrison of soldiers there. Perhaps she did something similar at Wednesbury, refurbishing a long-disused hillfort and turning it into a garrisoned stronghold? Placing a burh in such a location would have been consistent with her policy of strengthening her long frontier with the Danelaw (the part of England under Viking control). This frontier ran diagonally from the Mersey to the Thames and had divided the ancient Mercian lands since c.880. Proximity to the Roman road network was a key factor in Æthelflæd’s burh-planning and we may note that Wednesbury is close to the presumed line of a road running from the major highway of Watling Street. This route took a south-east alignment between the Roman forts of Water Eaton on Watling Street and Metchley near Birmingham, although its precise course in the Wednesbury area has yet to be confirmed.

If the Lady of the Mercians did indeed build a burh at Wednesbury, what did she call it? One possibility is that it might be the unlocated Weardbyrig (‘Watch Fort’) that she built in 915 according to the Mercian Register. A more ingenious theory relates to Wednesfield and the great battle of 910. It has been suggested that the name ‘Woden’s Field’ might not pre-date the battle (as is often assumed) but could have been coined in its aftermath. As both legendary royal ancestor and erstwhile war-god of the Anglo-Saxons, Woden would have been an appropriate figure to invoke in commemoration of a great victory over the Danes. Following the same train of thought, ‘Woden’s Fort’ on Wednesbury’s Church Hill might likewise have acquired its name around the same time, by virtue of being a landmark in a large area that had recently been renamed Woden’s Field. Or perhaps ‘Woden’s Fort’ was coined by Æthelflæd herself as a suitable name for a new burh within Woden’s Field? Such musings might not be as idle as they seem. Some historians do indeed wonder if the Mercian soldiers who fought in the Tettenhall/Wednesfield campaign were led not by Lord Æthelred – who appears to have been seriously ill at the time – but by his wife. Did Æthelflæd subsequently devise the name ‘Woden’s Fort’ to mark not only the English triumph at Woden’s Field but also the part she played in it?

Present-day Wednesbury has undoubtedly taken the Lady of the Mercians to its heart. Near St Bartholomew’s Church, a street called Ethelfleda Terrace preserves the Victorian form of her name, as does the nearby green space known as Ethelfleda Memorial Gardens. In the town centre, her image can be seen in public artworks created from stone and metal. At the main bus station she appears as one of two sturdy ‘caryatids’ supporting an arched gateway, while on nearby Holyhead Road she is depicted on a large mural as a spear-wielding warrior confronting a boatload of Vikings. There is no doubt that local people view her with affection, regardless of the uncertainty surrounding her connection with their town.

Wednesbury bus station: sculptured arch supported by ‘caryatids’ (Æthelflæd on the left; a worker from the tube-making industry on the right).

The Æthelflæd caryatid (see also the photo at the top of this blogpost).

(above and below) Mural sculpture on Holyhead Road, Wednesbury: Æthelflæd confronts Viking raiders.

Finally, we may note that the dedication of St Bartholomew’s church is of interest in the context of an Æthelflæd connection. We know that she was keen to promote and develop the cults of Anglo-Saxon saints, especially Mercian ones, among the people under her rule. One such saint was Beorhthelm who, according to old tales, had lived in Staffordshire as a monk and hermit in the early 700s. He is also known as Bertelin, and this is the usual form of his name in present-day churches dedicated to him. Some of these churches can justifiably claim to have been founded in Anglo-Saxon times, examples being St Bertelin’s in Stafford (adjoining the parish church of St Mary) and the parish church of Runcorn, now dedicated to All Saints but formerly dedicated to Bertelin. Another alternative form of the saint’s name is Bartholomew which in some cases took over the original dedication. This is what happened at Runcorn, where St Bertelin’s church eventually became known as St Bartholomew’s before being re-dedicated to All Saints in the nineteenth century. Might a similar process account for the name of St Bartholomew’s at Wednesbury, with the dedication having replaced an older one to Bertelin?

Stafford: the outline of St Bertelin’s Chapel beside the parish church.

Stafford and Runcorn are two old Mercian towns that originated as burhs founded by Æthelflæd, in 913 and 915 respectively. The original dedications of their churches are thought to reflect her promotion of Bertelin as one of Mercia’s premier saints. It is even possible that both churches were founded by her to serve the inhabitants of the new burhs. At Wednesbury, we cannot – on present evidence – be certain that she played any direct role in the town’s foundation. Nevertheless, the dedication of St Bartholomew’s parish church is certainly worth noting, and the possibility that it was originally known as St Bertelin’s can at least be kept in mind. Medieval records mention a church at Wednesbury in 1210, a building that may already have been old at that time. Whether a church existed as far back as the early tenth century is a question that archaeologists might be able to answer in the future.

* * * * *

Notes & references

Wednesbury is mentioned in my book Æthelflæd: the Lady of the Mercians as a possible Æthelflædan site and as one of the places where she is commemorated in public art.

Further information on Roman roads, place-names and Anglo-Saxon settlement in the area containing Wednesbury, Wednesfield and Tettenhall can be found in David Horovitz’s meticulous work Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians; the Battle of Tettenhall 910 AD; and other West Mercian studies (2017).

I’ve taken a look at the Anglo-Saxon history of nearby Wolverhampton in a recent blogpost on Lady Wulfrun.

Lastly, a curious item of local news from Wednesbury. The original brass plaque in Ethelfleda Memorial Gardens was stolen some years ago, as reported in an article from the Express & Star newspaper.

[All photographs in this blogpost are copyright © B. Keeling]

* * * * * * *